Varianta în limba română

Ieri am fost cu bicicleta „la colindat” la Remetea Chioarului, la mama și la tata. Venise și Paula cu prietenul, și toată lumea a pregătit masa de prânz în timp ce am stat la povești cu tata; l-am rugat să-mi mai povestească o dată despre celebrul deja „Johnny Complex”.

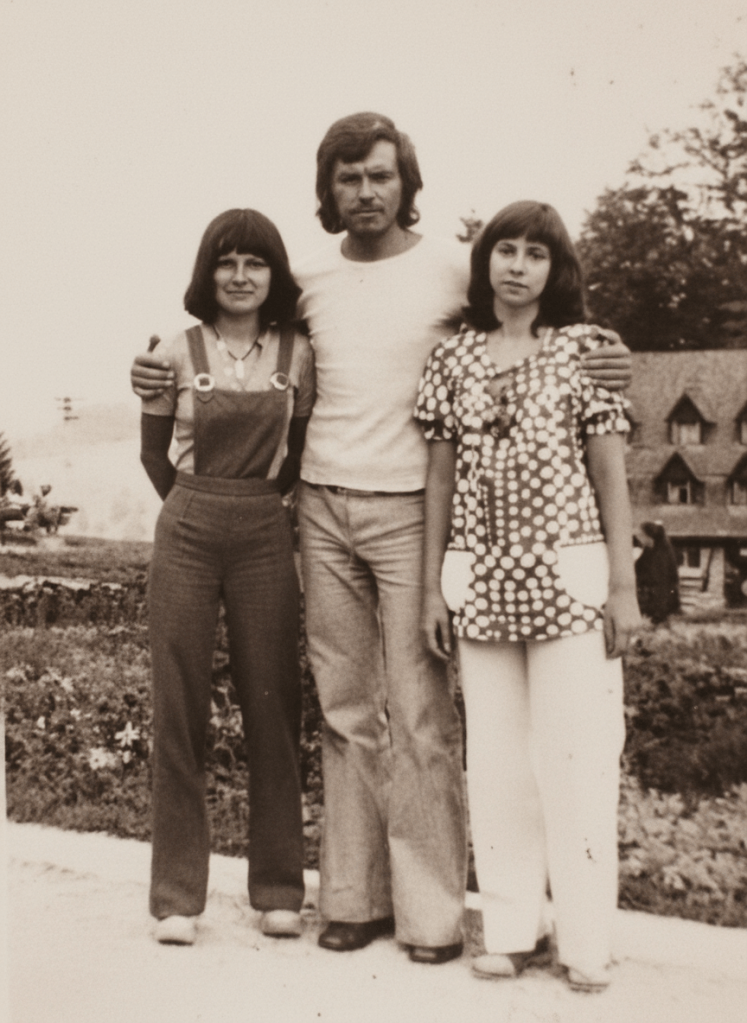

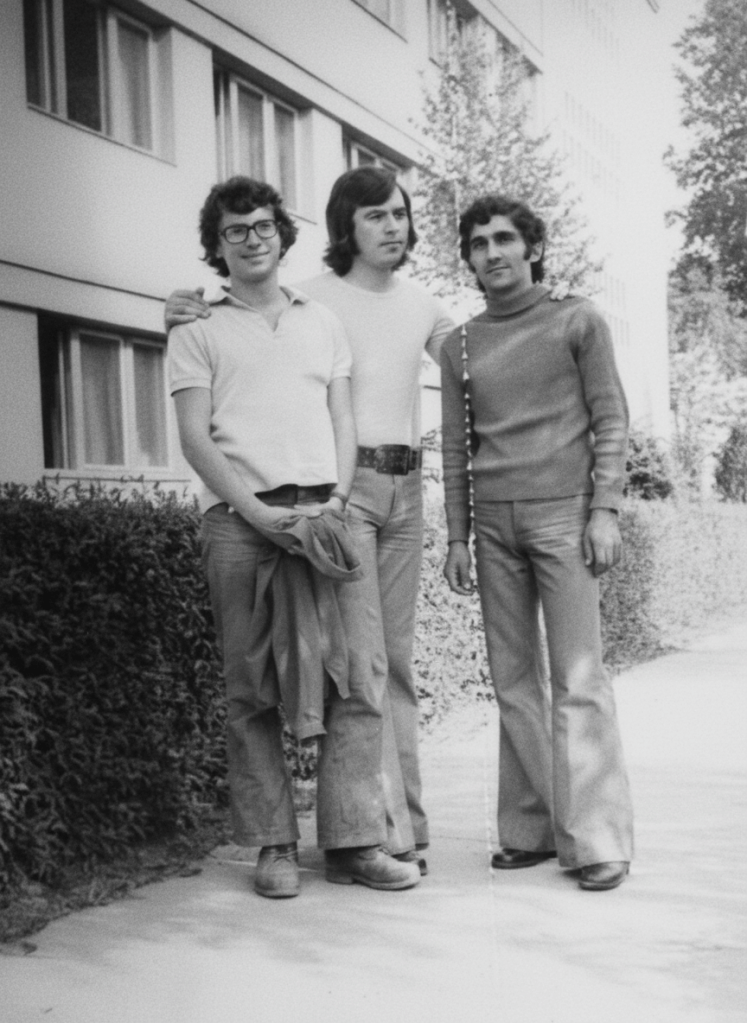

Tare m-a amuzat istoria asta în trecut, dar deja începeam s-o uit. În anii ’70 tata a petrecut 5 ani în Timișoara, în căminele Facultății de Construcții. Urma să devină inginer constructor, meserie care l-a purtat până la căderea Cortinei de Fier prin toată țara, an după an. Sunt mândru de el și de anii în care a muncit pe „șantierele patriei”, supraveghind construcția unor mari proiecte industriale.

Mai postam în trecut: părinții lui – bunicii – n-au avut deloc resurse să-l țină la studii nici în facultate și nici în liceu. A avut mare nevoie să câștige în fiecare an burse de merit ca să primească cazarea și cartela de masă gratuite. Din câte îmi povestea ieri, în anii ’70, când un salariu mediu era de 1500–2000 de lei, cartela pentru mâncare valora cam 500 de lei. O vindea de fiecare dată cu nițel mai puțin, ca să aibă bani de mici cheltuieli uzuale: șosete, tricouri, ș.a.m.d.

Apropo de haine, restul de bani de buzunar îi câștiga croind haine pentru ceilalți studenți, mai înstăriți. Se împrietenise cu o doamnă care cosea așternuturi pentru întreg căminul și aceasta îi dăduse cheile de la camera în care, atunci când avea comenzi, putea lucra la mașina de cusut a instituției.

Așa l-a cunoscut și pe „Johnny Complex”. Acesta îi comanda uneori pantaloni sau popularele pe atunci „salopete” pentru fetele din cămin sau de prin oraș. Pe Johnny îl găseai în complexul studențesc atunci când intrai în primul an de facultate și tot acolo îl lăsai, la finalizarea studiilor.

Era un mic afacerist, cumpărând de la traficanții de peste graniță tot soiul de „bunătăți” pe care studenții timișoreni le apreciau atât de mult. Ajunse de prin toată Europa, prin Iugoslavia și apoi în România: săpunurile, parfumurile, dresurile, jeanșii și alte obiecte atât de dorite de tineretul cochet și pus pe petrecere se vindeau repede și la prețuri avantajoase.

„Johnny Complex” găsise un confortabil echilibru acolo, în complex. Aranjase cumva să doarmă în camerele studențești, mânca probabil la cantină și rămânea în mod voit repetent, an după an, continuând cu mare abilitate și talent mica sa carieră de comerciant. Atent să nu fie exmatriculat, aranja probabil să „treacă” îndeajuns de multe examene și să „pice” atâtea cât era necesar ca să-și mențină poziția și statutul în comunitate.

Tata mi-a mai povestit și de faptul că viața studențească era vibrantă și că petreceri se țineau des în cluburile și discotecile din oraș. Timișorenii erau expuși la muzica radiourilor din toată Iugoslavia, pe care le „prindeau” la radiourile din camere la cea mai bună calitate. DJ-ii înregistrau probabil rock, disco, proto-electronică sau cumpărau viniluri prin traficul de graniță.

„Johnny Complex” este un exemplu de abilitate și spirit practic de care mulți români au dat dovadă în timpul anilor sub comunism. Cu ajutorul acestui fel de oameni, descurcăreți, cunoscând bine limitele între care puteau să se miște și să funcționeze, societatea românească a menținut în mod constant un contact, chiar dacă indirect, cu sfera de influență a Europei Centrale și de Vest.

Dacă această masă critică a dus – chiar fără să realizeze asta – o luptă subterană cu „status quo”-ul acelor vremuri și a erodat, an după an, imaginea falsă a „perfecțiunii orânduirii socialiste” proiectată de Partid prin propagandă și acțiunile lui coercitive, rămâne de răspuns de către cei care au trăit într-adevăr în acele vremuri.

English version

Yesterday I went cycling “caroling” to Remetea Chioarului, to my mom and dad. Paula also came with her boyfriend, and everyone prepared lunch while I sat and chatted with my father; I asked him to tell me once again about the now-famous “Johnny Complex.”

This story used to amuse me a lot, but I was already starting to forget it. In the 1970s my father spent five years in Timișoara, in the dormitories of the Faculty of Construction. He was on his way to becoming a civil engineer, a profession that carried him all over the country, year after year, until the fall of the Iron Curtain. I am proud of him and of the years he worked on the “construction sites of the homeland,” supervising the building of major industrial projects.

I had mentioned before that his parents—my grandparents—had no resources at all to support him financially, neither in high school nor at university. He depended heavily on earning merit scholarships every year in order to receive free accommodation and meal vouchers. As he told me yesterday, in the 1970s, when an average salary was 1,500–2,000 lei, a meal card was worth about 500 lei. He sold it every time for slightly less, just to have money for small everyday expenses: socks, T-shirts, and so on.

Speaking of clothes, he earned the rest of his pocket money by tailoring garments for other, wealthier students. He had befriended a woman who sewed bedding for the entire dormitory, and she had given him the keys to the room where, whenever he had orders, he could work on the institution’s sewing machine.

That is also how he met “Johnny Complex.” Johnny would sometimes order trousers or the then-popular “overalls” for girls from the dorm or from around town. You would find Johnny in the student complex when you started your first year of university, and you would leave him there as well when you finished your studies.

He was a small-time entrepreneur, buying all sorts of “goodies” from smugglers across the border—items that students in Timișoara greatly appreciated. From all over Europe, via Yugoslavia and then into Romania, soaps, perfumes, stockings, jeans, and other objects so desired by fashionable, party-loving youth would arrive, selling quickly and at advantageous prices.

“Johnny Complex” had found a comfortable balance there, in the student complex. He somehow arranged to sleep in student rooms, probably ate at the cafeteria, and deliberately remained a repeater year after year, continuing with great skill and talent his small trading career. Careful not to be expelled, he likely arranged to “pass” enough exams and “fail” just as many as needed to maintain his position and status within the community.

My father also told me that student life was vibrant and that parties were frequently held in the city’s clubs and discos. People in Timișoara were exposed to music from radio stations all over Yugoslavia, which they could receive on their dorm-room radios at excellent quality. DJs probably recorded rock, disco, proto-electronic music, or bought vinyl records through cross-border trafficking.

“Johnny Complex” is an example of the ingenuity and practical spirit that many Romanians displayed during the years of communism. With the help of such resourceful people, well aware of the limits within which they could move and operate, Romanian society managed to maintain a constant—if indirect—contact with the sphere of influence of Central and Western Europe.

Whether this critical mass waged—without even realizing it—a subterranean struggle against the “status quo” of those times, gradually eroding the false image of the “perfection of the socialist order” projected by the Party through propaganda and coercive actions, remains a question to be answered by those who truly lived through those years.

Leave a comment